The photos below are what we saw.

The

clipper Cutty Sark is docked at Greenwich. Built in 1869

it represented the pinnacle of British sailing technology and

held the record for fastest ship afloat for ten years.

After the Suez Canal opened, steam power took over and the Sark

came to dominate the sailing route to Australia. Given

more time, we would have loved to tour the ship.

The

walking route to the observatory passed the Maritime Museum and

this nice statue. We were pressed for time, so we did not

stop to investigate.

This

ship in the bottle is a scale model of Nelson's command

ship. The odd sail fabric is "artistic license".

We saw a

few of these food trucks in the London area. I think the

French made the truck in the 1950s and now they serve as rolling

kitchens.

I was

surprised by the continual jet noise but it turns out that

Greenwich is on the flight path for Heathrow.

The hill

that houses the observatory provides a commanding view of the

Canary Wharf area of metropolitan London.

Greenwich

is all about telling time and location. To know your

location, you must know your local time. Time is

referenced to the sun, but knowing time is key to calculating a

ship's location. Failure to have a good fix on ship's

location results in wrecks. After a number of tragic

wrecks with large losses of life and money, the British Admiralty

sought to solve the problem once and for all. The Royal

Observatory was part of that solution plan.

Standardizing

distance measures is critical for both location certainty and

repeatability in the construction processes for ships.

Exact

solar noon was measured at the observatory and communicated to

the outside world by dropping this red ball exactly at

noon. The sailors down in the flats on the River Thames

would synchronize their ship's clocks to the dropping of the

ball before heading out to sea.

The spike

on this monument points at the center of the earth's

rotation. The Prime Meridian, the zero point for

measurement of longitude, runs along the steel line in the patio

and through the center of the spike.

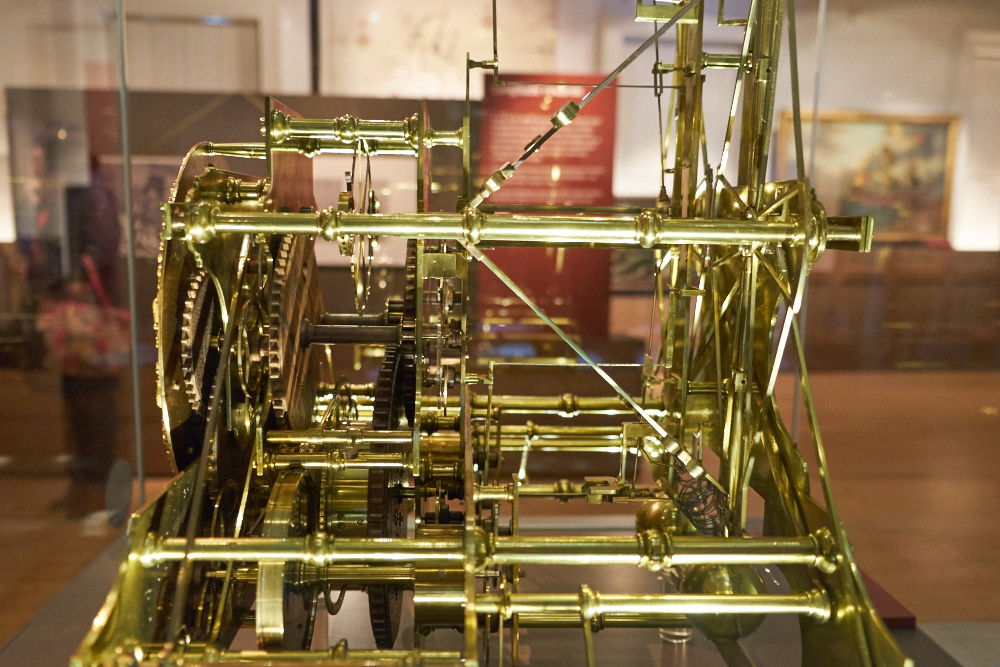

Knowing

when local noon occurs is useful, but to make that measurement

something more than a curiosity, you must be able to interpolate

time between successive noons. So, an accurate clock is

needed. Greenwich had many fine examples of old attempts

at building a precision measurement tool for time.

Each of

these two clocks were used by staff at the observatory to

measure the movements of the stars in an attempt to provide a

better way to locate a ship's position on the high seas.

The

large grandfather-style clocks kept reasonable time on

shore. But on the open seas, the rolling of the ship

destroyed the accuracy of the timing. The Admiralty

commissioned a contest to build an accurate timepiece that could

handle shipboard travel. The first attempt was John

Harrison's H-1 clock. The H-1 used counter-oscillating

masses to make it more resistant to ship's motion. And,

the H-1 was independent of the direction of gravity. Over

the years, Harrison's clocks got better and better, but still

eluding the huge reward for the challenge. In essence, the

Admiralty attempted to stiff him and Harrison petitioned the

King to get payment -- which he got. His efforts were an

important factor in Britain establishing naval superiority and

holding it for so many years. See

the Royal Observatory's page on this fascinating story.

Many

other clock designs were built and tested, but none so

transformatory as the Harrison line.

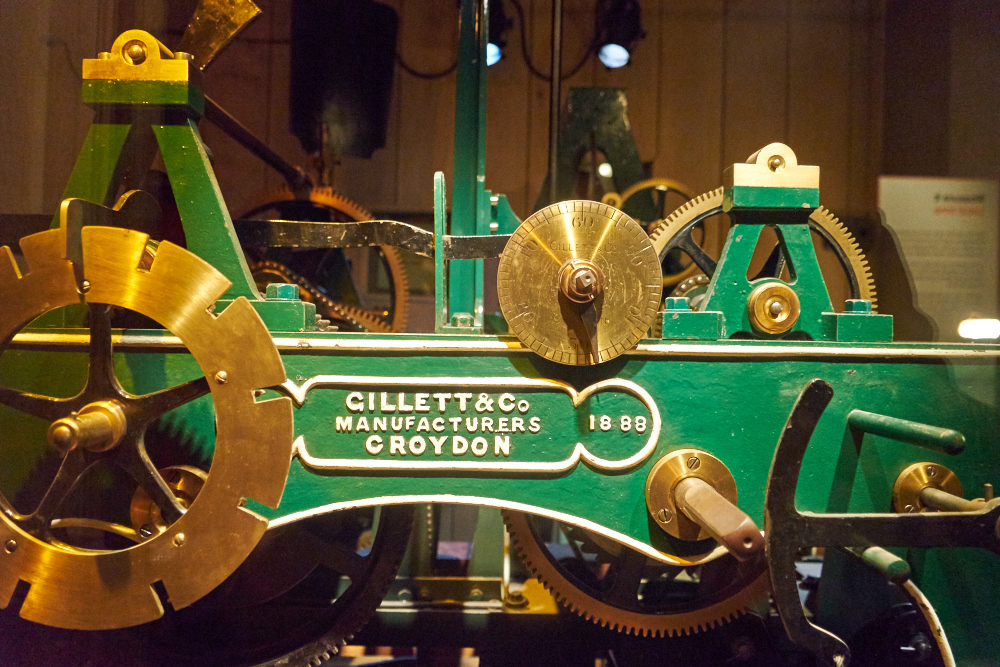

This is

a clock tower mechanism used to move the hands on large clocks.

Our time

in the museum was up and they ran us out. To return to

London, we had to take the Docklands Light Rail under the

Thames. The drill bit used to bore the tunnel was on

display at the station.

Pre-fabricated

sections of concrete were installed to make the final tunnel

lining. The lining can be seen in the photo above.

On the

north side of the Thames, we could see some newer structures

including this cool bridge.

The

Docklands and the Canary Wharf used to host a huge amount of

shipping. These dock cranes were left over from that era

and are now monuments.

After a

significant trip, we ended up back at Blackfriar's station and

back on the street. It was rush hour and the ubiquitous

double-decker buses were out in force.

| Previous Adventure | ||

| Trip Home Page |

Photos and Text Copyright Bill Caid 2015 all rights

reserved.

For your enjoyment only, not for commercial use.